Canadian Criminal Court System

Introduction

Security Guards need to be able to accurately identify and categorize offences and how to perform a citizen’s arrest. This section introduces the Criminal Code within the context of liability, duty of care and lawful authority.

This manual is a guideline and an aid for study, only. Many of the sections below are simplified for this purpose. The official statutes and case law should be consulted for exact wording and proper understanding.

The Criminal Code is a document containing most of the Criminal Offences in Canada and comes under the jurisdiction of Parliament, the governing body that sets our laws. It descends from other historical documents setting out laws, particularly the British North America Act, 1867.

Canadian Criminal Court System

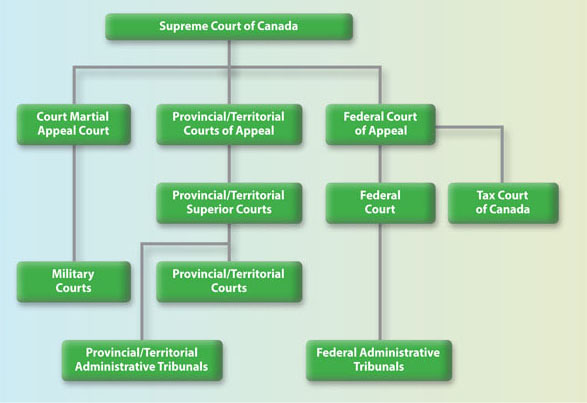

Our Courts are divided into four basic levels. Lower courts are bound by the decisions of higher courts, consistent with the principles of Case Law or “precedents.”

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Canada is the Apex court, and it comprises of nine Judges, referred to as Justices, with one of them serving as the Chief Justice of Canada. This highest judicial body in Canada is responsible for rendering decisions on appeals related to legal questions and also issues rulings concerning the constitutionality of laws enacted by Parliament.

Federal Court of Appeal

The Federal Court of Appeal is a Canadian federal court that primarily deals with appeals related to federal law and decisions made by federal administrative tribunals. It is the second-highest court in the Canadian legal system, just below the Supreme Court of Canada. The Federal Court of Appeal is responsible for reviewing and deciding cases involving matters such as immigration, intellectual property, taxation, and other areas governed by federal law. It plays a crucial role in ensuring the consistent application and interpretation of federal law across Canada.

Tax Court of Canada

The Tax Court of Canada is a specialized federal court in Canada that primarily deals with tax-related matters and disputes between taxpayers and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Here are some key points about the Tax Court of Canada:

The Tax Court of Canada is a specialized federal court in Canada that primarily deals with tax-related matters and disputes between taxpayers and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). Here are some key points about the Tax Court of Canada:

- Jurisdiction: The Tax Court of Canada has jurisdiction over a wide range of tax-related cases, including disputes involving income tax, goods and services tax (GST), Canada Pension Plan (CPP), Employment Insurance (EI), and other federal taxes and programs. It handles cases related to both individuals and corporations.

- Independent Adjudication: The Tax Court operates independently from the CRA. It provides a forum for individuals and businesses to challenge CRA assessments, decisions, and tax-related penalties. Taxpayers have the right to have their cases heard by impartial judges.

Federal Court Trial Division

The Federal Court Trial Division, also known as the Federal Court of Canada – Trial Division, is one of two divisions of the Federal Court of Canada, the other being the Federal Court of Appeal. Here are some key points about the Federal Court Trial Division:

- Jurisdiction: The Federal Court Trial Division has jurisdiction over a wide range of cases that involve federal law and issues falling under federal jurisdiction. This includes matters related to immigration, citizenship, intellectual property, admiralty, federal administrative law, and various other areas governed by federal statutes.

- Trial Court: The Trial Division primarily serves as a trial court where cases are heard and decided at the initial trial level. It deals with disputes, applications, and legal actions brought before it by individuals, organizations, or government entities. These cases can be civil or quasi-criminal in nature.

Ontario Court of Appeal

“In every Canadian Province and Territory, there are “Appellate courts” in place. These courts are responsible for reviewing the rulings made by Superior Courts and, when requested, offer guidance to the Provincial or Territorial Government, similar to the role of the Supreme Court at the federal level.

The Court of Appeal for Ontario handles cases related to various areas of law, including civil law, constitutional law, criminal law, and administrative law, such as matters related to the Private Security Investigative Services Act and other Ontario regulations. This court represents the highest level of appeals court within Ontario, unless a specific case is referred to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Decisions rendered by the Ontario Court of Appeal hold legal authority over all other courts operating within Ontario. Conversely, decisions made by a Court of Appeal in another province serve as more of a general guideline for lower courts, offering best practices rather than binding rulings.

Court of Ontario

The court of Ontario has two divisions, the Superior Court of Justice and the Ontario Court of Justice.

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

The Ontario Court of Justice, which was formerly known as the Superior Court of Justice, originated from the amalgamation of the High Court of Justice, District Court, and Surrogate Court in the 1990s.

The Superior Court of Justice is responsible for handling various legal proceedings, including divorce cases, lawsuits that fall outside the category of “small claims,” and the prosecution of indictable (more serious) offenses, which encompasses cases heard by a Judge and jury. Additionally, the Superior Court deals with appeals arising from Summary Conviction (less serious) cases.

Within the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, there exists a specialized division that manages small claims lawsuits where legal representation for the involved parties is not required.

Furthermore, this court is tasked with the review of decisions made by lower courts and plays a role in overseeing matters related to the Ontario Human Rights.

Tribunal, Ontario Labour Relations Board and so on.

The Superior Court also has a branch that deals exclusively with appeals and reviews of tribunal decisions called the Divisional Court.

Some family law cases are heard by the Ontario Court of Justice. These matters do not concern cases where there are claims regarding the division of property, child support and custody.

Ontario Court of Justice

The Ontario Court of Justice was previously called the Ontario Court, Provincial Division. This court is created under Ontario Provincial Statute and the jurisdiction is limited as a result. Most of these courts were formed from previous local courts that were historically presided over by Magistrates and Justices of the Peace, who were not necessarily educated as lawyers but appointed. Originally these courts were managed by municipalities.

The Ontario court of justice deals with summary conviction offences and family law matters except as noted above.

Family Law

Family law is a branch of legal practice that deals with matters related to family relationships, domestic issues, and interpersonal disputes. It encompasses a wide range of legal issues and concerns that arise within families and households. Here are some key aspects and topics within family law:

Family law encompasses issues like divorce, child custody, and financial support, and typically doesn’t pertain to the everyday responsibilities of a Security Guard. However, there are scenarios where Security Guards might encounter domestic disputes that lead to disturbances on the premises they protect. In such situations, it is advisable to engage the Police, especially if the dispute involves child custody or other contentious matters. Law enforcement authorities are better equipped to assess the legal aspects of these issues compared to private security personnel..

Municipal Court System

Security Guards may find themselves involved in the Municipal Court System, especially regarding parking violations, where they are required to provide testimony on behalf of the Crown if an accused individual decides to challenge the evidence presented by a Certified Contract Officer.

These proceedings are governed by the Provincial Offences Act and related Regulations and are overseen by a Justice of the Peace. The Defendant may not always be present in person and might be represented by an Agent, often a Paralegal practitioner rather than a lawyer.

In cases of parking infractions, the Defendant is consistently the company or individual registered as the vehicle’s owner. The prosecutor is employed as an agent of the city.

Court Procedures Preparation before appearing in court involves the following steps:

- Gathering all relevant paperwork and evidence, including reports, statements, videos, and memo books.

- Reviewing your case and notes, discreetly making additional notes about your trial attendance during appropriate times (not in the courtroom).

- Ensuring you have your subpoena and Security Guard License.

- Dressing in business attire.

- Taking a photograph of yourself in your full uniform.

- Ensuring you have no items that could be considered weapons on your person.

- Avoiding chewing gum or cough drops while in the courtroom.

When you arrive at court, follow these steps:

- Arrive early.

- Enter the “sanitary area” for security screening, emptying all metal objects from your pockets and placing them in the provided tray or basket.

- Put your Security ID on top of your subpoena, which should be on top of your other belongings for court security inspection.

- Be polite and friendly with court security and police, but maintain a professional demeanor. Remember that you are providing evidence on behalf of the Crown.

- Court security will follow their protocols and screen you as they would other members of the public and accused individuals. Choose your place in line carefully, considering potential conflicts with the accused, their friends or family, or individuals with a general dislike of authority. Avoid engaging in conversations or revealing your identity to those not officially connected to the court.

Once through security

To find the court docket for your case and locate your courtroom, follow these steps:

- Look for the court docket outside of each office, which may list cases by the name of the accused and provide information about the timing and order of trials.

- If you cannot find the docket outside the offices, visit the secure reception area at the Crown’s office. They can help you determine the room where your case will be tried.

- Try to locate any Police Officers who were present during the occurrence related to your case. Re-introduce yourself and inquire if they need to discuss any issues with you ahead of time.

- Identify the Crown Attorney for your case if possible. Approach them and ask if they have a few minutes for a short briefing before the trial. Keep in mind that they may be busy organizing their day and resources, so this may not always be possible. Nevertheless, it’s worth asking. Be sure to record the names of any police officers present and the Crown Attorney related to your case.

- Study the individuals in the vicinity of the courtroom close to the session’s start time to try and identify the accused (your subject). Sometimes, accused individuals may alter their appearance significantly by shaving facial hair, changing their hairstyle, or dressing more formally, especially if they have been coached by a lawyer.

After your initial preparation –wait near your room

Following your initial preparation, remain in the vicinity of your room.

Please be aware that it is highly unlikely for the accused to confront you, as most of these individuals are aware of the intense scrutiny they are under and may have received strict instructions from their lawyer, who will likely be close by their side.

Proceed to the waiting area near your courtroom and take a seat until the room’s doors are opened to the public. Keep in mind that you are likely under video surveillance and being observed by court security and police while waiting.

Maintain a state of alertness and vigilance for any individual who may attempt to engage you in a confrontation, even though this scenario is highly improbable. In the event of such an occurrence, employ polite, loud, and clear commands to ensure that police and court security can hear you. Use phrases like, “Sir, your comments are inappropriate. I do not wish to engage in a conflict; please move away from me immediately!” Position yourself defensively and distance yourself as much as possible from the individual, heading towards a more secure area, such as the vicinity of the entrance where screening is conducted (police and court security). Immediately report the incident to court security.

It is more likely that you may be approached by the defense attorney representing the accused (the subject), who may ask you questions about the case. In such interactions, maintain a friendly and positive demeanor. If someone who is not clearly affiliated with the Crown’s office or the police approaches you, inquire about their identity and whether they represent the accused. Refrain from discussing case details with them. Simply respond that you are willing to discuss any topic outside of the courtroom, except for the case currently before the courts. Inform them that you are prepared to provide testimony in court. You can then engage them in conversation about unrelated, non-controversial subjects, such as the “recent hockey game” or other news events.

When the courtroom doors open

Upon entering the courtroom, follow these steps:

- Find a seat in the public area, preferably close to the front but behind the first row. It’s a good idea to sit near the police officers or on the side of the witness box.

- Remove any overcoat you may be wearing but avoid draping it over the back of your seat. Keep your notebook in a suit jacket pocket or in your hand where you can access it easily. Hold your overcoat on your lap until you are called to testify, then leave it on the bench where you were sitting.

- Take off any non-religious headwear (hats) or sunglasses. Ensure your eyeglasses are clean, especially if you need them for reading.

- Be prepared for various court officials to approach you with questions or directions related to your role as a witness. They may discuss how the case will proceed and provide information about the expected duration of your case. Understand that the Crown and Defence Lawyer may discuss the matter and potentially adjourn the trial to another date or reach a settlement without a trial.

- If you are not approached, take the initiative to approach the Crown or another court official before the court session begins. Show them your subpoena and make them aware of your presence. They will likely review the document, confirm your presence, and instruct you to have a seat.

- Remember that everything you say in court, even if spoken in confidence to another person, may be recorded on the official court record. Maintain professionalism at all times.

Presiding officials

In provincial offences cases like trespassing, the court official you may encounter is often a Justice of the Peace. When you enter the courtroom, pay close attention to their introduction. When addressing a Justice of the Peace, it is appropriate to use the titles “Your Worship,” “Sir,” or “Ma’am.” In some rare cases, a Justice may be referred to as a “Magistrate.”

For Judges, who typically handle criminal matters, the correct titles to use are “Your Honour,” “Sir,” or “Ma’am.” In serious criminal trials, such as those held in the Supreme Court or jury trials, you may hear the term “Supreme Court Justice” or “Supreme Court Judge.” In these instances, the proper titles to use are “Your Lordship,” “Your Ladyship,” or “Sir” or “Ma’am.” Using the correct titles demonstrates respect.

In all cases, regardless of who you are addressing or who is addressing you in court, you cannot go wrong with “Sir” or “Ma’am.”

Court in session

As the scheduled start time for the court approaches, you’ll notice that conversations and general activities in the front of the court will diminish, and various officials will begin to take their positions. The presiding official, typically a Judge or Justice of the Peace (J.P.), depending on the case’s nature, will enter through a side door, dressed in robes. A court official will then call out, “now rise” or “all rise,” announce the judge or J.P., and declare the court in session.

Once the presiding official is seated, you may sit back down. It’s important to note that every time the judge enters or exits the court, such as for a recess, you must stand as a sign of respect.

If you need to leave the court at any time before or during the court session, do so in a manner that does not disrupt the proceedings, such as during breaks or when summoned outside by the police or a court official. When leaving, face the judge and bow at the door before departing. Additionally, be mindful not to let the doors slam, and close them quietly and carefully.

When/If you are called to testify

Stand up from your seat and make your way to the front of the courtroom, where you will be guided to the witness stand. Maintain an upright posture and ensure that you have your notebook in hand or readily accessible.

When speaking, project your voice clearly and audibly, avoiding shouting but using a tone suitable for public speaking, exuding confidence. When asked to state your name for the official record, provide your full name.

You will then be instructed to choose a holy book of your preference for taking an oath, such as the Bible or Quran, in accordance with your beliefs. If your religion prohibits taking an oath, you can request to make an affirmation instead. An affirmation is a solemn declaration allowed for those who have a conscientious objection to swearing an oath. It holds the same legal weight as an oath and will be permitted if you can explain that it is against your religious beliefs to swear an oath. This formal procedure is designed to ensure that you are bound to tell the truth. You will be asked if you swear or affirm to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Respond with a clear “I do.” It’s crucial to be completely honest and forthcoming when giving testimony in court, providing your account of events truthfully and answering all questions honestly. Failing to disclose relevant information or providing false statements can lead to a perjury conviction, which carries potential imprisonment. Additionally, being evasive, withholding information, or displaying inappropriate emotions, such as stubbornness, hostility, or antagonism, may result in a “contempt of court” conviction, also punishable by imprisonment.

Maintain a consistent public-speaking tone when delivering your testimony. Pause before responding to each question to allow the Crown the opportunity to object if necessary. Stick to answering the specific question asked, avoiding unnecessary details. Direct your attention to the legal representative who is posing the questions and then turn to address the Judge or Justice of the Peace when answering. If a question is unclear or requires clarification, respectfully inform the Judge or Justice of the Peace of your need for clarification. If the question cannot be answered with a simple “yes” or “no” and requires additional detail, convey this to the Judge or Justice of the Peace.

Strive to strike a balance in your tone. Avoid sounding too monotonous or overly emotional, finding a middle ground between these styles. Use your voice effectively to emphasize important points without letting emotions overpower your testimony.

Exercise caution when responding to questions framed with phrases like “I suggest to you.” For instance, a lawyer may say, “I suggest to you that you only arrested my client because you felt you were insulted.” Such questions imply that you acted unprofessionally and made the arrest due to feeling insulted or having your ego offended, rather than having valid grounds for the arrest. In such cases, your response should be, “No, that is incorrect.”

Testimony

The process of giving and answering questions during testimony typically involves three phases:

- Examination in Chief (conducted by the Crown Attorney).

- Cross-Examination (conducted by the Defence Attorney, representing the accused).

- Redirect or Re-Examination (conducted by the Crown Attorney).

When you find it necessary to refer to your notes (which is a professional practice), present your memo book before commencing your testimony in your own words. Politely request, “May I use my notes to refresh my memory, Your Honour/Worship/Sir or Ma’am?” If asked, clarify that the notes were made at the time of the case in question, responding with “At the time of the case in question, Sir (Ma’am).” On occasion, you may be required to provide your notebook to the Judge or Defence Counsel for examination.

The Crown Attorney typically initiates the proceedings with a series of brief introductory questions. These questions establish your connection to the case, the reason for your presence on the relevant day, your role, and other pertinent details. Once your introduction is complete and your association with the event is confirmed, they will usually pose an open-ended question, such as “Tell the court what happened?” When you begin narrating the events in your own words, it’s advisable to start with the following statement:

“”Your Honour, on [mention the date of the incident], I was employed as a uniformed Security Guard by [mention your security company’s name], contracted to provide security services to [state the name of your site], in accordance with the property management agreement with [mention your property management company’s name or the property manager’s name if available].

My responsibilities involved conducting routine patrols within the mall premises, ensuring the overall security and safety of the property, maintaining order, upholding peace, and enforcing the established rules and regulations as an authorized representative of the occupier [use these specific terms or similar ones, if possible].

At approximately [mention the time of the incident], I received a request for assistance from [describe who requested your help]. Here is what transpired…”

Please be aware that you might be asked if you possess a copy of the contract. In such a case, respond by stating that the contract is held by your company’s office, but clarify that there is indeed a service contract in place for [mention your site’s name].

Once all the questions have been addressed, and you are excused from the witness stand, kindly express your gratitude by saying, “Thank you,” bow to the Judge, step away from the stand, and return to your seat in the courtroom. If you are informed that you are not required to stay, you can indicate your preference to remain and hear the trial’s outcome for the purpose of submitting a report, as mandated by your employer.

Exclusion of evidence – exclusionary rule

The exclusionary rule stipulates that any evidence obtained in a manner inconsistent with the foundational principles of law should not be admitted as evidence during a trial. In other words, such evidence is “excluded” from the trial proceedings. This principle has been applied in various statutes and legal cases, setting precedents for judicial decisions.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as previously discussed in this manual, safeguards individuals against unreasonable search and seizure under section eight (8). Additional instances of this principle can be found in the Case Law section of this manual.

Physical evidence pertains to tangible objects or components of an object that are presented as evidence in a criminal case. Examples of physical evidence encompass items like fingerprints, stolen goods, weapons, shell casings, bloodstains, or DNA samples, among others.

Authentication is a procedure aimed at establishing the legitimacy of physical evidence while ensuring it has not been altered, falsified, or subjected to any form of tampering. This concept is closely intertwined with the idea of maintaining the evidence’s continuity, often referred to as the “chain of custody.” The chain of custody serves as a systematic approach to demonstrating which individuals have interacted with the physical evidence and outlining the manner in which it was managed from the moment it was initially discovered at a crime scene until it is ultimately presented for examination within a legal court proceeding.

Burden of proof

The burden of proof, known as onus probandi in Latin, refers to the responsibility of the prosecution (complainant) or defense (respondent) to provide evidence that reasonably supports the likelihood of the presented evidence being true.

In most instances, the burden falls upon the individual or entity making the complaint or pressing charges against another party. However, in specific situations, a “reverse onus” may apply, placing the burden on the accused or charged person to demonstrate that the alleged fact is untrue. An example of this legal concept can be found in the Trespass to Property Act of Ontario.

In essence, this implies that, in the majority of cases, the responsibility rests with the accuser or prosecutor to convince the fact-finder beyond a reasonable doubt of the case’s validity, while there is no obligation for the accused to establish their innocence.

The evidentiary burden, or the duty to present evidence, suggests that certain evidence introduced by one side in court is accepted as valid, placing the onus on the opposing party to prove that the related assumption is false.

Standard of proof

The standard of proof refers to the level of persuasion required to convince a court of the validity of a particular argument. This standard is applied in accordance with a hierarchy or scale as dictated by the legal rules under specific conditions or circumstances.

- Beyond a reasonable doubt: This principle mandates that the prosecution (Crown) must demonstrate that a collection of facts and circumstances has been presented, leaving no room for doubt in the mind of an ordinary, prudent, and cautious person (the average person) regarding the accused’s guilt of the offense.

- Preponderance of evidence or balance of probabilities: This standard is employed in civil cases and suggests that a set of facts or circumstances is more likely to be true than not.

- Clear and convincing evidence: Commonly used in the United States, this concept requires the party with the burden of proof to convince the court that a collection of facts or circumstances is more likely to be true than not.

- Reasonable and probable grounds: Reasonable grounds refer to a collection of facts and circumstances that would lead an average, prudent, and cautious person to strongly believe in a matter, surpassing mere suspicion. In essence, the average and reasonable person would have faith in these circumstances.

- Reasonable doubt: Reasonable doubt can be defined as doubt based on reason and common sense, which fully satisfies or entirely convinces the fact-finder regarding a matter. In some instances, such as in the case of R v. Majid in England, the appeal court favored the term “sure the defendant is guilty” over “satisfied beyond all reasonable doubt” in the lower court’s jury instructions.

- Reasonable suspicion: This concept is closely linked to “articulable cause” or a collection of objectively discernible facts that would provide a person with reasonable cause to believe that someone is clearly involved in a crime.

- Air of reality: This is a test that assesses whether a defense case stands a chance of success if all the facts claimed by the defendant are assumed to be true.

The Best Evidence Rule, as currently practiced in Canada, applies exclusively to documentary evidence. This rule has its origins in English common law and is referenced in both American and Canadian courts. The case of Omychund v. Barker from 1745 is often cited, where English Judge Lord Hardwicke stated that evidence would only be admissible if it represented “the best that the nature of the case will allow.”

The Best Evidence Rule is often closely connected to the authentication rule. The fundamental idea is that the best evidence is the original document, provided it is available. If the original is not available and all original copies have been destroyed, then a copy can be admitted as evidence if it accurately reflects the content of the original and if the original was destroyed by the opposing party in bad faith. Copies are typically supported by testimony confirming their accuracy in reflecting the original.

Originally, this rule served as an exclusionary principle, and today it is still in effect. If an original document is accessible, it must be presented in court rather than providing a copy for presentation.

Documentary Evidence

Documentary evidence Incorporates formal legal texts, statutes, parliamentary rulings, and other documents related to government and legal procedures. According to the Canada Evidence Act and Ontario Evidence Act, documentary evidence also includes specific types of records such as banking records and official business records maintained in accordance with regular business practices. This category covers records like your evidence notebook or memo book, along with any other reports or records generated as part of daily activities.

This category encompasses evidence that has been documented, recorded, or stored. It includes materials like papers, journals, cards, pictures, audio recordings, movies, video tapes, computer records, and so forth. Specialists will scrutinize this form of evidence to ensure its authenticity and quality. For instance, a video recording might have unclear visuals or audio, handwriting may be hard to decipher, or a photograph could be in deteriorated condition. In such cases, these document types might not be considered trustworthy evidence.

Testimony Evidence

Testimony, in this context, refers to statements or declarations made by a witness under oath or affirmation. Testimony can include personal narratives, especially in civil cases. Testimony is subject to scrutiny through questioning and corroboration, meaning it should be supported by other similar evidence.

Testimony may also be supported by forensic evidence, circumstantial evidence that meets legal criteria, and visual recordings, among other forms of evidence. Courts assess the weight of testimony based on the quality of the evidence presented and consider it in light of the established criteria and tests.

Opinion Evidence: In contrast to evidence that relies on a witness’s personal knowledge or specific facts, opinion evidence involves a witness expressing their thoughts, beliefs, or deductions regarding the disputed facts. The opinion must be grounded in facts that have been presented as evidence.

Many common situations and everyday experiences allow most people to provide their opinions. For instance, individuals can offer a reliable opinion on whether someone appeared intoxicated on a specific occasion, even without medical expertise, based on their observations of intoxicated individuals on previous occasions.

However, when opinion evidence is presented during a trial, it doesn’t automatically mean that a judge must accept it without question. Just like any other form of evidence, once the opinion is deemed relevant and helpful, the judge must then determine its significance. The judge may choose not to assign any weight to the opinion.

Forensic Evidence

Forensic science constitutes an academic and scientific field closely connected to investigations and the legal system. It encompasses a systematic approach for deducing facts from diverse forms of evidence collected through this method.

Forensic evidence encompasses various categories, such as handwriting analysis, interpretation of bloodstain patterns, identification of firearms and ammunition, analysis of fingerprints, examination of trace evidence like fibers, blood type matching, DNA analysis, identification of tool marks, scrutiny of skid marks, document analysis, computer forensics, pathology (the study of diseases), entomology (the study of insects), and more.

The fundamental principle underlying forensic science is the recognition that the physical environment, including all entities, including humans, interact with one another. Consequently, evidence related to an event, no matter how minuscule or challenging to discern, is invariably present. Once this interaction is identified and substantiated through scientific methodologies, conclusions about what transpired can be objectively demonstrated, typically with a degree of “moral certainty” regarding the events, as assessed by an expert.

Security guards must exercise caution in relation to these matters, as valuable forensic evidence can easily become contaminated, leading to inaccuracies or rendering it useless if proper care is not taken.

Hearsay Evidence: Hearsay evidence refers to a statement that was initially uttered by a person who is not the witness testifying during the trial and is presented to establish the accuracy of the original statement.

For instance, if a witness provides testimony that, while at work on Tuesday, Mr. Smith informed them that he witnessed Bill assaulting the victim, and the intention behind the witness’s testimony is to demonstrate that the accused committed the assault, then Mr. Jones’s statement is considered hearsay.

Hearsay evidence can be uncertain in terms of reliability because the individual who originally made the statement is not present for questioning..

Circumstantial Evidence

Circumstantial evidence refers to proof of certain facts that, in turn, lead to the inference or deduction of other facts through logical reasoning. This type of evidence indirectly establishes a fact and requires the court to draw conclusions based on the available information.

Unlike direct evidence, which directly pertains to a fact in question, circumstantial evidence is information that demonstrates facts or circumstances from which one can draw inferences regarding the existence or non-existence of the fact in question. For example, a witness who saw the accused person stab the victim provides direct evidence, while evidence suggesting that the accused had a knife, possessed gloves similar to those found near the victim, and was observed in the vicinity shortly before the stabbing offers circumstantial evidence.

One aspect of concern when dealing with circumstantial evidence is its reliability. For instance, if the ground is wet, it might lead one to infer that it rained. However, this isn’t the sole possible conclusion, as heavy dew or the use of a sprinkler in the area could also explain the wetness.

It’s not mandatory for each piece of circumstantial evidence to conclusively point to the accused’s guilt in order to be considered. Circumstantial evidence, like other forms of evidence, can be utilized either independently or in conjunction with other evidence to establish guilt or innocence.

Direct Evidence

In contrast to circumstantial evidence, direct evidence provides straightforward support for a claim of truth. For example, when a witness testifies that they personally witnessed someone committing a crime, it constitutes direct evidence. This differs from situations where an expert testifies, based on forensic evidence like DNA, that they are morally certain a person committed a crime.

This involves a witness testifying about something they perceived through their five senses, directly related to a fact in question. For instance, when a witness observes an assault and testifies that the accused person was the one who struck the victim.

Among the various types of evidence presented during a trial, direct evidence provided by a testifying witness is the most preferred.

Just like other forms of evidence, the judge must assess the weight to assign to direct evidence. Several factors can influence the reliability of direct evidence, including the witness’s ability to perceive, remember, and describe the events accurately. Furthermore, the clarity of the questions asked can also impact the quality of the witness’s evidence. Judges must consider these factors when determining the evidential weight.

To assess the reliability of direct evidence, it is possible to question the witness. Questioning by the accused, Crown, or judge can help evaluate not only the witness’s credibility but also identify any factors that might affect the reliability of their evidence, such as the witness’s consumption of alcohol before witnessing the event or unfavorable lighting conditions.

Physical Evidence / Real Evidence: This category pertains to tangible objects that are presented during court proceedings or demonstrations within the courtroom. Typically, a witness introduces such a physical object and provides details about where it was discovered, the circumstances of its discovery, and how it has been preserved since its discovery. For instance, let’s consider a scenario where a book with the accused person’s name on it was found at the location of an assault. The witness would need to explain precisely where the book was located, how it was found, and the measures taken to securely preserve it, ensuring it remained unaltered prior to the trial.

By itself, physical evidence is considered circumstantial. Simply because the book belonged to the accused does not conclusively prove the accused’s involvement in the assault. When physical evidence is combined with direct evidence, such as a witness testifying that they observed the accused throwing the book at the victim, the evidence becomes more dependable.

Witnesses – Including Expert Witnesses

In the context of the Canadian Legal System, a witness is an individual who directly observes or perceives a crime or violation and subsequently provides testimony in court or swears an affidavit or other legal statement. These individuals possess firsthand knowledge of the incident in question.

Expert witnesses, on the other hand, are typically recognized by the court due to their demonstrated expertise in a specific area relevant to the case. These experts may have specialized knowledge in fields such as science, forensic science, law, or the use of force, and their testimony is considered valuable in providing insight and analysis related to the matter before the court. . This could be educated persons in fields of study such as science, forensic science, law or use of force, etc.

Continuity of evidence

The Continuity Rule, also known as the chain of custody in the legal context, pertains to the handling of documents or other items intended to be presented as exhibits in court. This rule ensures that the evidence remains securely stored and in someone’s possession at all times until it is formally introduced in court. The witness who plans to submit physical evidence must be able to confirm that the item they are presenting is the same one they initially acquired or took control of. For example, if you seized a cassette tape that an accused individual did not pay for or a weapon they used to threaten another individual, you must be able to affirm that you maintained control over the item until it was brought into court.

The court must be convinced that there was no tampering with the item to change its condition or substitute it with a different item. This assurance can often be achieved by either physically holding the item or storing it in a secure location, like a locked cabinet, where no one else can access it. Alternatively, you could enclose the item in a container and seal it with your signature, demonstrating that it remained unaltered and secure in your absence. In some cases, the item may simply be photographed, and the photograph carefully safeguarded.

In the legal realm, this concept is crucial and is known as the “chain of custody.” It involves a series of measures aimed at demonstrating that an object or physical evidence linked to a case has been appropriately handled and remains untampered with throughout every stage of the process, from its initial discovery in public to its presentation in court. Specific protocols, including the proper handling, secure storage, and meticulous documentation of the evidence, must be adhered to for it to be admissible in a trial. How a Security Guard manages physical evidence or safeguards a crime scene can carry significant consequences, making it imperative to exercise the utmost care in preserving evidence related to crimes at all times.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Let’s Summarize

Private Investigator and Security Guard Act

Sets out guidelines in addition to the regulations set forth by the Standing Orders and Post Orders. Every security guard shall wear a uniform while acting as a security guard. Every security guard while on duty shall carry the prescribed identification card issued to him or her under this Act and shall produce it for inspection at the request of any person. Failure to comply with these regulations may result in a maximum $2,000 fine and cancellation of your license.

Canadian Criminal Court System

Provincial courts try most criminal offences and, in some provinces, civil cases involving small amounts of money. Provincial courts may also include specialized courts, such as youth courts, family courts and small claims court. The provincial governments appoint the judges for provincial courts. Superior courts, the highest level in a province, have power to review the decisions of the provincial or lower courts. The federal government appoints the judges to these courts, and their salaries are set by Parliament. Superior courts are divided into trial level and appeal level. The trial level hears civil and criminal cases and has authority to grant divorces. The appeal level hears civil and criminal appeals from the superior trial court. These levels may be arranged as two separate courts:

The trial court is named the Supreme Court or the Court of Queen’s Bench and the appeal court is called the Court of Appeal. In some provinces there is a single court, generally called a Supreme Court, with a trial division and an appeal division.

The Supreme Court of Canada serves as the final court of appeal in Canada. Its nine judges represent the five major regions of the country, but three of them must be from Quebec, in recognition of the civil law system. As the country’s highest court, it hears appeals from decisions of the appeal courts in all the provinces and territories, as well as from the Federal Court of Appeal. Supreme Court judgments are final. Ordinarily, parties must apply to the judges of the Supreme Court for permission (or leave) to appeal. In certain criminal cases, the right to an appeal is assured.

Definitions:

The Law is a body of rules that regulates the conduct of members of society, and is recognized and enforced by the Government and its agents.

The Courts are a place where serious offenders can be convicted and punished and at the same time to ensure that the innocent and the unfortunate are not oppressed.

THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA

The Supreme Court of Canada is the final court of appeal from all other Canadian courts. The Supreme Court has jurisdiction over disputes in all areas of the law, including constitutional law, administrative law, criminal law and civil law.

Federal Court

The Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal are essentially superior courts with civil jurisdiction. However, since the Courts were created by an Act of Parliament, they can only deal with matters specified in federal statutes (laws).

PROVINCIAL/TERRITORIAL COURTS

Each province and territory, with the exception of Nunavut, has a provincial/territorial court and these courts hear cases involving either federal or provincial/territorial laws.

Provincial/territorial courts deal with most criminal offences, family law matters (except divorce), young persons in conflict with the law (from 12 to 17 years old), traffic violations, provincial/territorial regulatory offences, and claims involving money, up to a certain amount (set by the jurisdiction in question). Private disputes involving limited sums of money may also be dealt with at this level in Small Claims courts. In addition, all preliminary inquiries (hearings to determine whether there is enough evidence to justify a full trial in serious criminal cases) take place before the provincial/territorial courts.

Military Courts

These courts hear cases involving the Code of Service Discipline for all members of the Canadian Forces as well as civilians who accompany the Forces on active service. The Court Martial Appeal Court has the same powers as a Superior Court.

Preparing for a Court Appearance

All Security guards who are requested to attend court to testify and give evidence, must ensure they are prepared, with all the relevant materials pertaining to the case at hand.

Some of the Common Materials Required are:

- Memo Book – Notes taken at the time of the incident in question

- Report – the subsequent compiled information after the investigation has been completed.

- Barr Notices – this is any documentation to support the case. Any other relevant material such as videos, digital recordings, photographs etc.

Once you are aware that your attendance is requested, you are to initiate the collection process of all documents used relating to the case.

Check with your company and the site location where the incident occurred. Tell them you request the material for court and arrange a time to retrieve the material.

This should be done well in advance of the court date, in case any material is missing.

What should I do if I have to testify in court?

You may receive a document that tells you to appear in court to give evidence. This document is called a subpoena, and it will tell you exactly when you must be present in court to testify. This document is an order, not a request. Even if you change jobs, the subpoena is still in force. If you fail to appear, a material witness warrant may be issued for your arrest.

You will likely be called as a Crown witness. That means you will testify against someone who is accused of committing a crime. First, you will be questioned by a lawyer for the Crown (Prosecutor), then by a lawyer for the accused (Defense). It is important for you to present a professional image and to convince the court that the evidence that you are giving is reliable.

Preparing for court

- Familiarize yourself with the rules and etiquette of the court.

- Carefully review all of your notes. Be sure of the time of day, date, and location where the incident took place. The company will give you your reports to look at.

- Go over the order in which the events happened, and try to remember exact details, such as weather conditions, license numbers, lighting etc.

- Speak to the Crown about what they want to bring out in your testimony and what kinds of questions the Defense lawyer may ask you.

- Make sure your uniform is clean and ironed and that you are well groomed

Tesitfying in court

Try to arrive early in case the Prosecutor has questions to ask you before you testify. This will also give you time to relax before you are called to the witness stand. If you can’t arrive early, make sure you arrive on time.

Turn off your cellphone

Stand or sit up straight. Do not slouch or lean on the side of the witness box. Look at the lawyers when they question you, and direct your answers to the judge or jury.

Speak loudly enough for everyone to hear you and slowly enough for the judge to take notes.

Do not answer more than the question asked. The answer to “When you arrested him, did he say anything?” is “Yes,” not “Yes, he said he didn’t do it.”

Give the facts, not your opinion. Do not say, “He was looking around to see if anyone was watching him.” You could say, “He looked around often.” If either lawyer objects to a question, stop. Do not answer until the court rules on the objection.

If you do not know the answer to a question, say so in a direct way. Avoid phrases like “I guess” and “I think.”

Read from your notes only if necessary and if allowed by the judge. Your testimony should be from your memory and you should refer to your notes only for very specific details, such as someone’s exact words. The notes are used to refresh the guard’s memory of the events.

Use a polite, reasonable tone. If you say, “He had some CDs that he forgot to pay for,” your tone is sarcastic, and your testimony may not be taken seriously. It is not a crime to forget to pay for something.

Show equal respect for both the Prosecutor and Defense lawyers. It is the Defense lawyer’s job to question your reliability. Don’t take it personally. If you feel yourself getting angry, keep a neutral expression on your face.

Do not leave until the judge excuses you.

Remember, as a witness at a criminal trial, the role of the security guard is to advise the court what the guard knows about the case being tried.

Duty of Care

Definition:

A duty of care is a legal duty to take reasonable care not to cause harm to another person that could be reasonably foreseen. … In public liability law, a person can only sue for injury or damage if someone breached a duty of care they owed to the injured person.

Legal Requirements

During emergencies and everyday situations you have a duty of care towards the people you serve and are trying to help. You may also be asked to hold on to a piece of evidence before transferring possession of it to a peace officer.

What this means to you as a Security Guard: While providing First Aid, CPR or assisting otherwise, you may not quit or give up. You are obliged to continue providing help until you are relieved of your duties. Your relief might be a fellow guard or a paramedic, but you do not stop unless you have a replacement. No Exceptions!

For evidence purposes, you may not transfer any evidence to anyone other than a people officer (Police). Always take note of who received it from you. You may not lose sight of this evidence, so do not leave the area, do not give it to anyone else, or ask someone to watch it for you. Continuity of possession is vital for criminal cases and a piece of evidence that has lost this continuity is worthless.

You are legally obliged to keep records and pass on any evidence to a policer office and no one else.

The three most basic kinds of evidence that courts consider are Direct, Real and Documentary Evidence.

TYPES OF EVIDENCE:

Direct Evidence: Direct evidence is the testimony of a witness with respect to something that witness perceived with one or more of their five senses and which directly relates to one of the facts in issue. For example, when someone witnesses an assault and gives testimony that it was the accused who struck the victim. Of the different types of evidence which may be presented at trial, direct evidence provided by a witness testifying is preferred. Like any other form of evidence, the judge must determine what weight should be given to direct evidence.

Various factors can affect the reliability of direct evidence including the ability of the witness to perceive what he/she is testifying about, the witness’ ability to recall the event and the witness’ ability to express and to describe what was observed. In addition, understanding the questions asked may also affect the witness’s evidence. Judges must consider the presence of any of these factors when deciding how much weight to give the evidence.

The reliability of direct evidence can be tested by questioning the witness.

Questioning by either the accused or the Crown or the judge can assist in determining not only the witness’s credibility but also whether any factors exist that affect the reliability of the witness’s evidence, such as the fact that the witness had consumed alcohol prior to witnessing the occurrence or the existence of poor lighting conditions.

Documentary Evidence: This is evidence that was written, recorded or stored. This includes items such as documents, notebooks, cards, photographs, sound recordings, films, videotapes, computer records, etc. Experts will examine this type of evidence to make sure that it is real and of good quality. For example a video recording may have an unclear picture or sound, handwriting may be difficult to read, or a photograph may be in poor condition. These types of documents may not be accepted as reliable evidence.

Physical Evidence / Real Evidence: This includes physical objects that are shown in court demonstrations done in court. A witness usually introduces a physical object and explains where the object was found, how it was found, and where it has been kept since it was found. For example, suppose a book with the name of the accused on it was found at the scene of an assault, The witness would have to explain exactly where the book was found, how it was found and how it has been kept safe, where it could not be changed in any way, before the trail.

Physical Evidence by itself is only circumstantial. Just because the book belonged to the accused. IT doesn’t prove that the accused committed the assault. If the physical evidence is used with direct evidence such as a witness saying they saw the accused throw the book at the victim, then the evidence will be more reliable.

Circumstantial Evidence: Unlike direct evidence that relates directly to a fact in issue, circumstantial evidence is evidence which proves facts or circumstances from which the existence or non-existence of the fact in issue may be inferred.

One concern about circumstantial evidence is its reliability. For example, if the ground is wet, one may infer that it rained. However, this is not the only possible conclusion; there could have been heavy dew or a sprinkler may have been used in the area.

It is not necessary that each piece of circumstantial evidence lead inevitably to the conclusion that the accused is guilty in order to be accepted. Circumstantial evidence may be used like other types of evidence either in isolation or in conjunction with other evidence to determine guilt or lack of guilt.

Hearsay Evidence: Hearsay evidence is a statement originally made by someone other than a witness testifying at trial and which is submitted for the purpose of proving the truth of the original statement.

For example, if a witness gave evidence that at work on Tuesday, Mr. Smith told her he saw Bill punch the victim, and the purpose behind the witness’s evidence is to prove that the accused assaulted the victim, then the statement of Mr. Jones is hearsay.

Hearsay evidence may be of questionable reliability because the person who made the original statement is not present to be questioned.

Admissions: Voluntary admissions made by an accused and reported by another witness, fall outside the hearsay rule and may be admissible.

Evidence Act

There are two Evidence Acts. These are:

- The Canadian Evidence Act

- The Ontario Evidence Act

Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act

As a Security Guard in Ontario you will be governed under the Provincial Evidence Act for most of the offences that you will deal with that are of a serious nature. The collection of and presentation of video evidence is regulated by both the Ontario Evidence Act and PIPEDA. More than likely the only evidence you will have to give will be from the issuance of Parking Enforcement activities in traffic court.

WHAT CAN I DO TO MAKE SURE THE CRIME SCENE IS PROTECTED?

If you are the first one at a scene of a crime, you may be called to give evidence in court about what you saw when you first arrived.

Crime scenes need to be preserved and left untouched until police arrive. In a way this is similar to your duty of care for evidence. Think of any of the CSI shows you have seen on TV. An undisturbed crime scene makes it possible for Police to conduct an investigation without worry of evidence contamination.

While you are waiting for the police: get medical attention for anyone who needs it take notes of anything you see, hear or smell. Make sure you record the time draw diagrams to make your notes clearer write down the names and addresses of any witnesses, and any information they give you. Ask them to stay at the scene until the police arrive include a description of anyone suspicious that you see near the crime scene make sure no one enters the scene to damage or remove evidence. You could set up a barrier with tape or anything else available, or keep a door closed protect trace evidence such as footprints, tire prints, cigarette stubs, etc. If the weather is bad, you could use a plastic sheet to cover this evidence escort all authorized people, such as fire or ambulance personnel, to the scene write down the details of any changes that were made to the original scene.

WHEN THE POLICE ARRIVE:

make sure you know who is in charge, and turn the responsibility for the scene over to that person. This is important because the court will need proof that there was no break in the chain of people in charge of guarding the evidence: complete your notes. Include the name of the person in charge and their badge number and the time when they took control of the scene; help the police as needed, then return to your normal duties.